The Ladder of Inference is a concept developed by organizational psychologist Chris Argyris which stipulates that we live in a world of self-generating beliefs that remain largely untested. We adopt those beliefs because they are based on conclusions, which are inferred from what we observe, plus our past experience. The ladder represents the mental process individuals go through when moving from observed data to drawing conclusions, and illustrates how people unconsciously make assumptions based on limited (and often incorrect) information, which then shapes their beliefs, actions, and interactions.

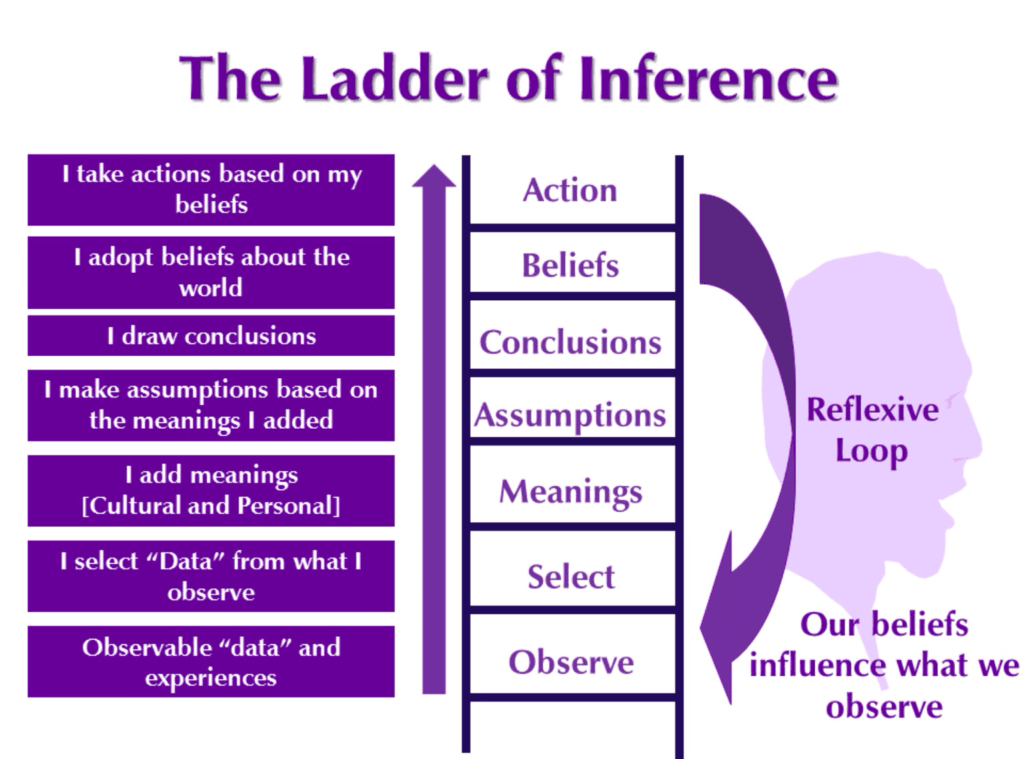

The Ladder of Inference consists of several steps or rungs that are traversed in order:

- Observation: At the bottom rung of the ladder, we have observed data or information. This includes raw facts, sensory input, and actual experiences that are available to us.

- Selecting Data: From the observed data, we tend to select certain information based on our personal filters, biases, and prior experiences. We focus on specific elements that align with our existing beliefs or expectations.

- Interpreting Data: Once we have selected specific data, we start interpreting it by adding meaning and making assumptions. We begin to give significance to certain information and draw conclusions based on our personal beliefs and values.

- Making Assumptions: Assumptions are beliefs or theories we form based on the interpreted data. These assumptions may be conscious or unconscious and can heavily influence our thought process and subsequent actions.

- Drawing Conclusions: Based on our assumptions, we draw conclusions or make judgments about a situation or person. These conclusions may be incomplete or biased due to the limited information we have considered.

- Adopting Beliefs: Over time, the conclusions we draw from the ladder of inference shape our beliefs. These beliefs become ingrained and influence our perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors.

- Taking Actions: Finally, our beliefs lead to actions. We behave in ways that align with our beliefs, reinforcing and perpetuating the cycle of the ladder of inference.

By understanding the process and consciously examining the steps on the ladder, individuals can become more self-aware, improve their critical thinking skills, and make more informed decisions based on a broader and more accurate understanding of the situation. It also encourages individuals to be open to different viewpoints, suspend judgment, and engage in dialogue to uncover shared meaning and avoid the pitfalls of making hasty and biased conclusions.

Using the Ladder of Inference

Individuals can improve their communication by using the Ladder of Inference in four ways:

- Making their thinking and reasoning more visible to others (advocacy).

- Becoming more aware of their own thinking and reasoning (reflection).

- Inquiring into others’ thinking and reasoning (inquiry).

- Examining beliefs that may have been taken for granted to see if they are based on facts (research).

The following inquiring questions can help break the cycle and promote more open-minded, critical thinking:

- What is the observable data behind that statement?

- Does everyone agree on what the data is?

- Can you run through your reasoning?

- How did we get from that data to these abstract assumptions?

- When you said “X,” did you mean “(my interpretation of X)” or something else?

An Example of the Ladder of Inference Thought Process

Alex and Jordan are back again from the previous articles in this series. This time Jordan is making a presentation to the executive team about the new product features they’ve added for the upcoming release. While everyone else is engaged and asking questions, Alex stares off into space and yawns. At the end of the presentation, Alex doesn’t ask any questions, but interrupts to suggest that they should all really see a demo of the features.

Here’s what’s going on in Jordan’s head…

- Observation: I see Alex slouching at the table, drinking coffee, not making eye contact, and yawning.

- Selecting Data: I zero in on the lack of eye contact and the yawning.

- Interpreting Data: Those things mean that Alex is bored and not paying attention.

- Making Assumptions: Alex was bored by my presentation and thinks I’m incompetent.

- Drawing Conclusions: Alex is out to sabotage my involvement in the project.

- Adopting Beliefs: Alex hates me and wants to see me fired so they can run all the projects the way they like without my interference.

- Taking Actions: I’m not going to share any more of my ideas with Alex or invite them to any more meetings.

The more that Jordan believes that Alex is an evil person, the more they reinforce their tendency to notice Alex’s antagonistic behavior in the future. This phenomenon is known as the “reflexive loop”: our beliefs influence what data we select next time. And there is a counterpart reflexive loop in Alex’s mind: as they reacts to Jordan’s strangely antagonistic behavior, they’re probably jumping up some rungs on their own ladder. For no apparent reason, before too long, they could find themselves becoming bitter enemies.

Alex might indeed have been bored by the presentation, or they might have been eager to show off the awesome work the two of them did together. Alex might think Jordan’s incompetent, or might be exhausted from staying up late last night, or might be worried the exec team isn’t sold on the new features and want’s to offer some more proof. But Jordan can’t know, until they find a way to check their conclusions. Because Jordan has been making multiple trips up the ladder, though, they might not feel the psychological safety to outright ask Alex if the presentation was boring or useless.

Jordan stops and takes a deep breath, realizing they’ve been climbing the ladder quite a bit. They ask Alex to stay behind after the end of the meeting so they can chat. Alex asks some open ended questions:

- Test the observable data: That was quite the yawn during the meeting!

- Select other data: I noticed you drinking a lot of coffee, late night?

- Ask for data: What did you think of the presentation?

- Test an assumption: Were you bored in that meeting?

- Test a conclusion: Are you enjoying working on this project with me?

Alex gives another jaw-cracking yawn and says, “Oh, not bored! I was up so late last night working on the demo that shows off all the fabulous new features! I was hoping to give the exec team a taste of what our customers will experience so they’ll approve that next phase of the project where we’ll iterate on those additional feature mock-ups. You really saved the day by combing up with that incredible idea that enabled us to fit in three more features!”

Alex, apparently, is not out to get Jordan, have him kicked off the project, or get him fired.

꧁༺ ༻꧂

The ladder of inference explains why most people don’t usually remember where their deep-seated attitudes and beliefs came from. The original data is long since lost to memory after years of making inferential leaps, and the belief itself is now treated as the data. Since the journey up the ladder of inference is one that takes place solely in your head, it requires a level of self awareness to step back and break the cycle. You first have to accept that you’re always going to draw meaning and inferences from what others say and do, based on your past experience, filters, and world views. If we did not use past experience to help us interpret the world, we would be lost. Nobody would be able to ‘learn from experience’ at all. You can still draw on your experience, but do so in a way that allows you to check back on assumptions about others’ behavior.

A final word of caution on deciding what’s a fact and what’s not… Don’t let your memory trick you. No matter how obvious it seems, a fact isn’t really substantiated until it’s verified independently by more than one person’s observation, or by a physical record (a video recording, picture, voice Slack message, etc).