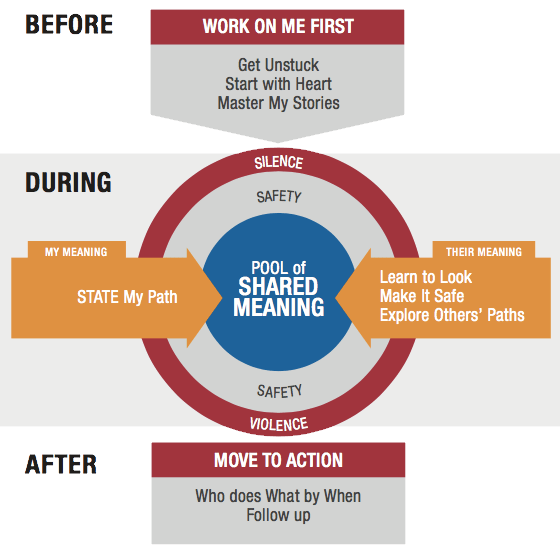

The Crucial Conversations model is a framework developed by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler in their book “Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High.” It provides numerous tactics and a structured approach to handling difficult and important conversations effectively.

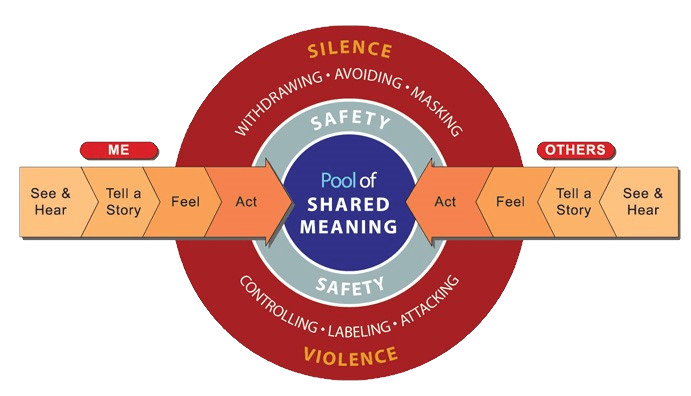

A crucial conversation is one in which stakes are high, opinions vary, and emotions run strong. In these types of conversations, the model posits that people have a default reactive position of “silence,” withdrawing, avoiding, or masking or “violence,” controlling, labeling, or attacking. The goal of the model is making it so that everyone feels safe to contribute their unique perspective to the conversation, find a common goal to collaborate around, and reach a mutually agreeable outcome.

Using the Crucial Conversations Model

The model consists of seven key elements, most of which are broken out into sub-components with tactical suggestions:

- Start with Heart: Begin the conversation by clarifying your intentions and examining your own motives. Focus on what you really want to achieve and ensure you approach the conversation with a positive mindset. Avoid going off track or falling for zero-sum choices.

- Learn to Look: Recognize when the conditions for a crucial conversation occur. It is important to keep the lines of communication open and avoid falling into “silence” or “violence.” Encourage the sharing of ideas and perspectives.

- Make It Safe: Create a safe environment where everyone feels comfortable expressing their thoughts and opinions without fear of negative consequences. Foster mutual respect and establish ground rules for the conversation. If trust and safety has been breached, recover it by:

- Apologizing when you’ve violated respect.

- Use do/don’t contrasting statements to fix misunderstandings. For example, “I don’t mean to imply that you aren’t a dedicated employee, but I do need to you to finish this project by Friday.”

- Finding mutual purpose by identifying the underlying goal that is common between you. If one doesn’t exist, invent a mutual purpose by moving to more and more widely encompassing goals, e.g., “We all want the company to do well.”

- Master My Stories: Our personal stories and interpretations can impact how we perceive situations and people’s intentions. Learn to recognize and challenge your assumptions and be open to different interpretations. Consider why a reasonable, rational person would hold an opposing opinion. Understanding how people get from observation to action can be broken down into multiple steps reminiscent of the Ladder of Inference discussed in one of the previous articles in this series:

- See and Hear: First we observe what others do.

- Tell the story: Based on the facts we observe, we tell a story about why someone else is behaving that way.

- Feelings: The story we tell ourselves about the other people involved drives our emotional reaction and the feelings we have in situation.

- Act: Finally, our feelings drive our actions.

- STATE My Path: Clearly express your views, concerns, and goals. Use “I” statements to avoid sounding accusatory and communicate your thoughts in a respectful and constructive manner. STATE is a nemonic which stands for:

- Share your observed facts

- Tell your story of your motivations and how you feel

- Ask for others’ paths so you understand their feelings and motivations

- Talk tentatively instead of framing things in absolutes to help keep the discussion flowing

- Encourage testing by asking curious questions

- Explore Other’s Paths: Actively listen to others, seek to understand their perspectives, and ask open-ended questions to encourage them to share more. Be genuinely curious about their thoughts and experiences.

- Use AMPP tactics to get other people talking: Ask questions to start the conversation; use Mirroring to confirm others’ feelings; Paraphrase their statements to acknowledge their stories; and Prime the conversation with ideas when the conversation seems stalled.

- When it’s your turn to talk, remember your ABCs: Agree on important points; Build a common goal by pointing out areas of agreement, and then add elements that were left out; and Compare opinions by describing how your ideas differ rather than theirs being wrong.

- Move to Action: Engaging in dialogue is not making a decision. Focus on finding a mutually agreeable solution or action plan. Look for common ground and brainstorm potential options. Determine who does what, by when and commit to follow-through to hold yourself and others accountable.

An Example of the Crucial Conversations Model In Action

The two software engineers from the previous articles in this series, Alex and Jordan, are having a heated disagreement over the design of their new software feature. They both have drastically different ideas of how complete and robust the feature should be for the initial release of the software to the customer. Alex thinks they should start with minimal functionality for a larger number of things, and Jordan thinks they should start with more complete functionality for fewer things. Alex thinks that Jordan is showing incompetence by not following best practices for iterative design, and Jordan thinks that Alex reckless for not focusing on the needs that the customer actually paid for. Here’s how they might use the Crucial Conversations model to come to a resolution.

As soon as their meeting starts, they’re both entrenched in their old arguments. Alex’s voice gets louder, talking over Jordan, and Jordan crosses their arms and refuses to say anything more. They’re firmly in the space of a crucial conversation, and they’ve already breached the zone of safety and gone to “violence,” and “silence.” They’ve forgotten what the real point of this project was (delivering features for a paying customer) and are telling themselves stories to paint the other as the villain.

Alex realizes that they’re getting nowhere and calls for a ten minute break so that they can do a bit of a reset. Jordan recommends that they try out the Crucial Conversations model to see if that will help them get anywhere.

While they’re grabbing a drink and a snack, they both take a moment to take a few deep breaths and think about the outcome they really want for themselves, for the other person, and for the company. They try to go back into the meeting trying for a more positive mindset, assuming that the other must have some valid reason for their viewpoint. Jordan apologizes to Alex for sulking, and Alex apologizes for interrupting.

Alex says, “Look, I’m not trying to imply that your ideas are without merit here, but I’ve been in this industry for 20 years, and I’m trying to enable us to get quick feedback from the customer by only doing the bare minimum for a bunch of things they might want. I don’t want us to build something that’s not going to add value for them.”

Jordan responds, “And I want to make sure that we deliver the functionality that we know they’ve asked for not of additional things that may only be nice to haves. What’s a goal that we can both agree on?”

“Well, we’re both trying to bring value to the customer and protect the reputation of the company,” says Alex.

“And I want each of us to feel good about the features we do deliver,” says Jordan. “Given that, let’s put our heads together and see what we come up with,” concludes Alex.

Jordan thinks that Alex does have a lot of experience, and customer feedback is really important. Sometimes customers claim they want one thing, but really need something else they haven’t even been able to conceive of, never mind clearly articulate. Maybe Alex is looking out for everyone’s best interests by taking this quick and shallow coding approach.

Alex thinks that Jordan may have a point about being sure to deliver the fully functional features the customer has already asked for. If they don’t, the customer may stop funding their development efforts and they’ll lose the contract.

They decide to lay out what they’ve observed and the details of their reasoning:

- Alex had put several features into the technical design after talking to the Product team, but without getting confirmation from the customer that the features were desired.

- Jordan had put comments in the technical design stating that this might be the wrong direction, but Alex marked those comments as resolved without replying to them. This left Jordan feeling ignored and frustrated.

- Jordan deviated from the technical design and wrote more extensive code for the smaller set of features they were focusing on. Alex felt like their industry experience had been discounted and their authority as the lead on the project had been ignored. Alex confirmed being angry about this and saw it as an intentional slight.

Seeing that Alex was heading towards the edge of the zone of safety, Jordan tried another contrasting statement to try to restore things, “I wasn’t trying to slight you, in fact I really value your experience; I just wanted to make sure we had something more complete to show the customer for the next demonstration so we could get their feedback.”

“Okay, I think we had the same goal of getting feedback at the demonstration,” said Alex “How were you envisioning showing them possible alternatives to make sure they didn’t want something else?”

“Ah,” said Jordan “my plan was to use some mock-ups instead of writing code to show them other possibilities. That would save us a bunch of time and still give the customer a taste of what else was possible. But I was so focused that I didn’t communicate that, so I understand if you felt like I was intentionally ignoring you.”

“Oh, I admit I didn’t pay close attention to the comment you added to the technical design when I was closing all of them before the presentation to the team. I was in a rush and had already planned to write more minimalistic code. Seeing paper mock-ups is different than being able to interact with the features on the screen, but not a bad idea. You’re right about it being less time-intensive,” said Alex.

“Okay, so what should we do going forward,” asked Jordan.

“What if I take over doing the mock-ups for a few other potential features and you focus on getting a bit more functionality for the four features they’ve asked for,” asked Alex.

“We’re still aiming for the demonstration next week to get their feedback, right?”

“Actually, I think we can get away with the basic code I wrote for the most important features and some mock-ups for the demonstration next week. That should give you some more time to focus on writing more complete code for those four important features for the demonstration in three weeks. That way you aren’t as rushed,” said Alex.

“Great,” exclaimed Jordan, “Let’s check back in on Monday, two days before the next demonstration, just to make sure we’re still aligned and things are going as planned.”

Feeling like they understood the other person’s viewpoint helped calm both of them down so that they could focus on the real challenge at hand, making the customer happy. They ended the meeting with a plan and clear expectations of who was contributing what towards the success of their shared goal. Their relationship still felt a little bruised, but they felt much better about each other than they had in weeks, having heard the other person’s side of the story.

꧁༺ ༻꧂

Mastering the art of crucial conversations is a valuable skill that can have a profound impact on our personal and professional lives. By employing this model, we can transform difficult interactions into opportunities for growth, understanding, and resolution. This framework empowers us to navigate high-stakes conversations with confidence by maintaining an open mind. By starting with the heart, staying in dialogue, creating a safe environment, and actively listening to others, we can forge stronger connections, build trust, and achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.

One response to “Constructive Conflict Framework #7: The Crucial Conversations Model”

[…] The Crucial Conversations model, which focuses on high-stakes, emotional conflict. […]

LikeLike